"Humorous all my life! Lord! It's enough to drive one crazy from sadness!" - Ostap Vishnya

The security forces came to arrest the humorist Ostap Vysnya. On December 26, 1933, they visited the Kharkiv house "Slovo," where he lived with his wife, actress Varvara Maslyuchenko, and her daughter from a previous marriage, Maria (home called her Murochka). There were also dogs— a whole room dedicated to hunting dogs. One of them, Tsya, was “the size of a good calf”. She always greeted guests warmly, leaving bruises on their legs from her tail, which was as hard as a piece of wire.

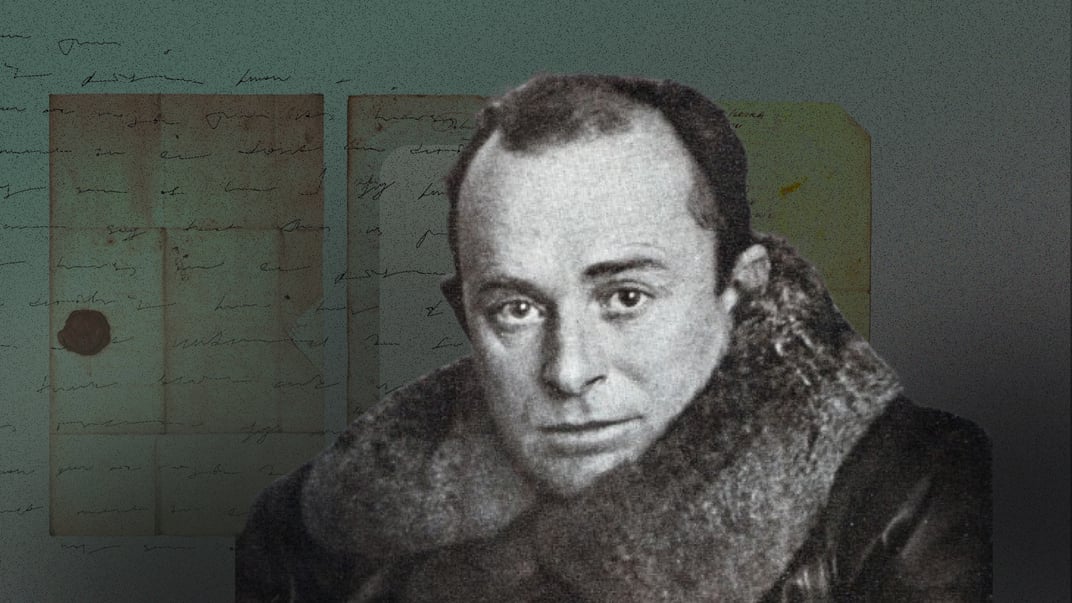

The 44-year-old Vysnya, with “already a short hairstyle that resembled baldness, with slightly bulging kind eyes”, turned pale but remained calm. He asked his wife for fresh underwear. She loaded him up with a pillow, clothes, books, an unfinished translation of a play, and the last 40 rubles that were at home. One of the newcomers undressed and settled down at the writing desk in the office like a landlord. He graciously allowed them to take whatever they asked for.

Before putting on his coat, the writer entered the restroom and closed the door. One of the guards yanked it open and stood behind him.

On the threshold, the housekeeper Sonya lamented: “Where are you taking the master?” Vysnya calmed her down. Once he was taken away, a search began in the house.

On the next day, the investigator announced that the arrest was not a misunderstanding and accused the humorist of counter-revolutionary activities and terrorism. Allegedly, he was a member of the "Ukrainian Military Organization" and intended to assassinate the second secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Pavlo Postyshev.

Vysnya considers this nonsense and jokes in response to the questions during the interrogation.

— In which room were you planning to shoot the leader of the people?

— I prefer to kill leaders in the fresh air!

Already three weeks later, in his testimony, he agrees with everything he was accused of.

The prosecutor sends the case of "Gubenko, also known as Ostap Vysnya" to the judicial troika for consideration.

The suggestion is— "EXECUTION".

Several Happy Years in Kharkiv

Pavlo Gubenko could have been killed much earlier. For instance, in 1920, when he was imprisoned for having served in the army of the Ukrainian People's Republic. Moreover, he was a high-ranking officer: under his leadership in Petliura's army, all railway hospitals were filled with typhus-stricken soldiers from the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Ukrainian Galician Army.

There were many torture chambers in the basements where Chekists shot people without much discrimination. A few months later, he was literally pulled out of there by Vasyl Ellan-Blakytnyi, who had a reputation as a literary producer and real power. He helped some young talents with housing, and others with jobs.

Pavlo Gubenko was taken in as a columnist for the newspaper “Izvestia VUTSIK”. He transformed into Ostap Vysnya. Many writers of that time used pseudonyms. There are many versions as to why Vysnya was chosen: perhaps he loved berries, or perhaps it was inspired by “Sadyk vishnevyy kolo khaty,” or maybe it was simply for aesthetics.

Since then, he would enjoy several happy years in Kharkiv, experiencing almost everything: the love of readers, the authorities, and the woman he loves. He would gain fame and wealth, but never freedom. Vysnya would never feel free.

He would always be monitored and reported on. Even those closest to him. His long-time friend Yuri Smolich, who later wrote fascinating memoirs about Vysnya, and Pavel Tychyna, his neighbor from the "Slovo" house, would report on whom he celebrated the New Year with, what they talked about, what woman he lived with, where he worked, and with whom he drank.

Here is a report from Tychyna's "agent" from October 1928, after the humorist returned from Germany and Poland, where he had been treated: “Ostap Vysnya, during a meeting with his friend Lebedenko, almost cried and, looking up, said: ‘What a wonderful thing freedom is, you know, our Soviet Union is a prison, and Europe is paradise.’” “And seeing all this, will you be the bard of the red gentleman?” asked Lebedenko. “What can I do, such is my dog’s fate,” Vysnya sadly replied.

“So who is the all-Ukrainian elder?”

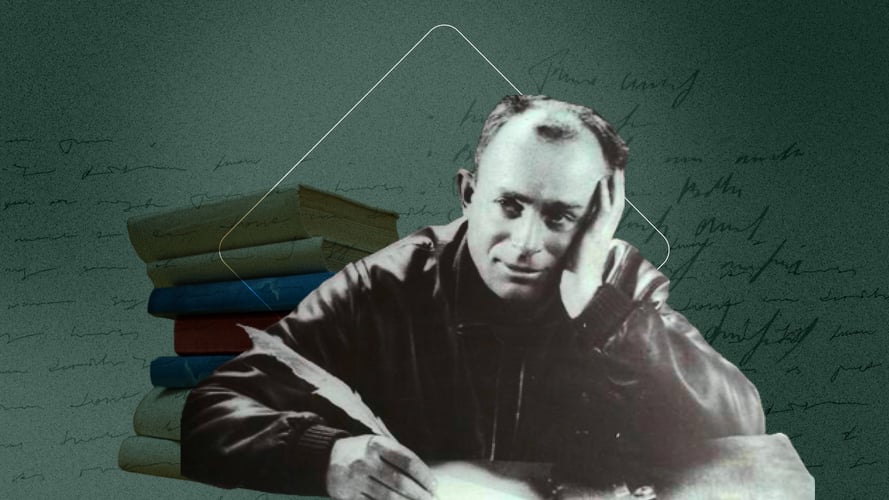

Vysnya is aware of the surveillance. But life takes its course: young, energetic, talented, and very hardworking; his “smiles”— a genre he created himself— are published in every all-Ukrainian newspaper. Books are being released one after another, by 1928 there are 25 collections, which will soon be combined into a four-volume set! The total print runs reach up to a million copies— the second place after Taras Shevchenko. For this, he is called the “king of print runs.”

“I really want my people to smile, to smooth out at least one wrinkle on their foreheads. Lord, how simple everything is,” writes Vysnya.

His simple, unpretentious humor is well-received. Readers eagerly await his smiles, and newspapers without them are not even worth opening. To read them, some learn to read, while others master Ukrainian.

So, what is the secret?

He is cheerful, sincere, open, and naturally witty. One acquaintance recalled: “You would enter a room, and you would immediately know where Pavlo was sitting. Laughter erupted from there every minute.”

His cousin Mykola Balash wrote: “Pavlo knows how to tell stories very skillfully, he knows a multitude of jokes, and he just keeps throwing out quips. It was already 4 a.m., and we were still awake because the stories and jokes were so funny, and I kept asking: ‘Tell me more, Pavlo.’”

Myk Johansen spoke of Vysnya: “99% of Ukrainians are those who, upon seeing a new Vysnya smile and not even knowing its content, already clutch their stomachs, fall to the ground, and roll around, desperately pleading: ‘Oh, let me read it quickly so I at least know what I'm laughing at.’”

He classified the remaining 1% as those who do not acknowledge Vysnya's talent, regarding his work as cardboard and primitive.

“Smirking condescendingly, they take some of Ostap Vysnya’s columns and begin to read them aloud, unable to contain their laughter from the second sentence. While doing so, they disdainfully command: ‘Well, I told you— it’s so silly that one cannot help but laugh.’”

The writer becomes a favorite among Ukrainians not only because of his humor. He is one of them— a friend who listens and helps, a defender: he receives bags of letters, and people seek audiences with him. The chairman of VUCIK, Hryhoriy Petrovskyi, joked: “So who is the all-Ukrainian elder— me or Ostap Vysnya?”

“Oh, I will run away!”

“The marriage did not bring any special joys. Quite the opposite. Don’t think there are any ‘family misunderstandings,’ no. Everything is well on that front. Even too well. And you know, a quiet nest is not for someone like me. I am not made of that material. So you sit there and turn and twist: every day it’s coffee after coffee! But sometimes you just want to shout: ‘Give me kvass at least once! At least beet kvass!’ It tears me inside. Oh, I will run away! Oh, I will run away!”

This is how Ostap Vysnya wrote to his cousin about his first marriage. Early and bland for him. His passionate nature craved for passions. He went to the circus every evening, never missed new movies and premieres in all the city theaters.

There he saw the young actress Varvara Maslyuchenko, playing Joan of Arc. He was captivated by her “beautiful figure of a slender French warrior-maiden.” Friends joked that he almost jumped from the balcony onto the stage. During intermissions, he would run to support the debutante in the dressing room.

The beauty was divorced,