"You shouldn't be hunched over in grief but stand tall in honor." What are the issues with military cemeteries in Ukraine?

From Tradition to Soviet Fashion

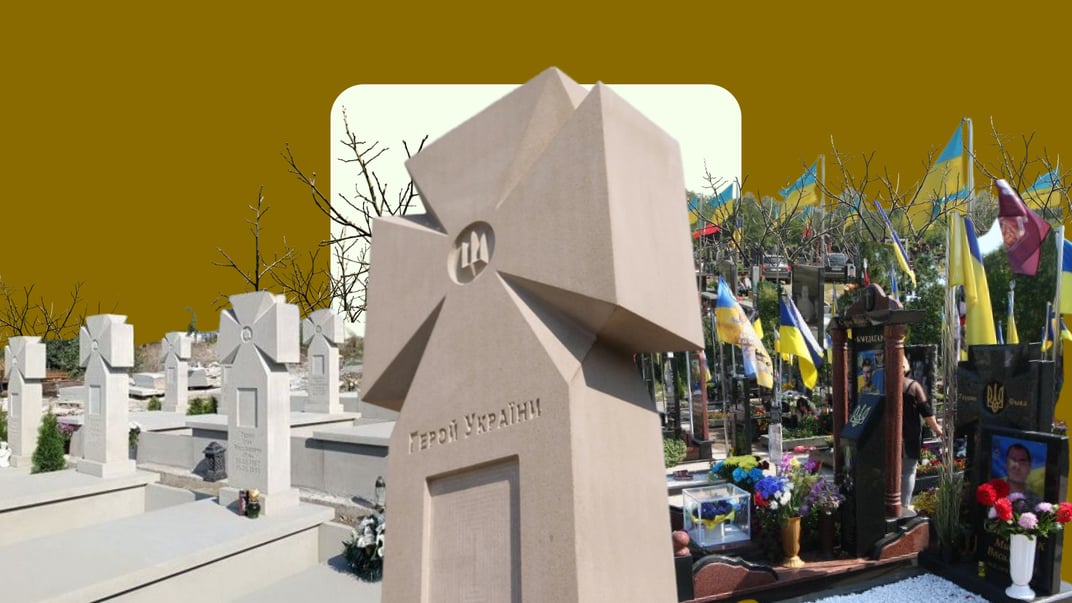

Dark and gloomy—this is how Ukrainians perceive most military cemeteries. Although the monuments in military burial sections vary in color and shape, the overall atmosphere of tragedy is typical.

“In most cases, military cemeteries differ from ordinary ones only by the flags that stand next to the graves, because this polished granite is just a tribute to a trend that has dominated the funeral industry for the last 40 years,” says local historian Roman Malenkov.

Roman is a researcher of Cossack cemeteries. He notes that granite was not used in Ukrainian tradition in the past. It is a fairly strong but difficult-to-process material. The surface of polished granite is sensitive to climatic conditions. Over time, the inscriptions carved into the stone become unreadable. To make them last longer, the surface is polished. As a result, it looks unaesthetic, Malenkov states.

Today, granite is the most commonly used material for making monuments, including those in military cemeteries. The local historian believes that the owners of processing enterprises working with granite have monopolized the market. Therefore, seeing sculptures made of sandstone or limestone, which are more characteristic of Ukrainian tradition, has become a rarity in cemeteries today.

These are not just memorials. They are objects that evoke memory and should be works of art. In most communities, this is not considered. They simply treat them like ordinary cemeteries, the only difference being that they place flags next to these graves.Roman Malenkov, local historian, researcher of Cossack cemeteries

Cemeteries from World War I that have survived to this day demonstrate a European tradition characterized by a rather ascetic and modest form of the cross or tombstone, as well as a clear structure of the cemetery itself. With the advent of Soviet power, cemeteries took on a more chaotic and oppressive appearance. By habit, they continue to be built this way even now.

“If we talk about the current time, unfortunately, we have a bit of chaos here. On one hand, this is due to the fact that at the state level, this matter has not been properly regulated until now. On the other hand, we have mass burials, a huge number of casualties, and this process is so large-scale that it is indeed difficult to control,” noted architect Ivan Shchurko in an interview with hromadske.

The Golden Standard Looks Modest

The grave of a hero should be a visual, emotional, and ideological extension of his military service, according to Ivan Shchurko. Therefore, the form of the tombstone and how well it tells the story of the person and his deed are very important.

Unfortunately, nowadays, in villages and small towns, we encounter “kitsch”, oversaturated with colors and forms [military cemeteries]. These graves create a very questionable quality chaotic collection of elements. The army is about clarity, structure, logic, and asceticism. Therefore, these military cemeteries should also not have unnecessary elements.Ivan Shchurko, architect-planner

One successful example of modern military burials is the “Pantheon of Heroes” in Ternopil. It is already being used as a model by other communities.

The concept's author, Dartsya Veretyuk, told hromadske that while developing the project, she studied foreign experiences as well as “pre-Soviet” Ukrainian traditions. This allowed the cemetery to be created from which “you don’t want to run away with all your might.”

All these dark granites and this sorrowful melancholy that hunches you over when you visit, this hopeless sadness, is characteristic only of the post-Soviet space—at least from what I’ve seen. Around the world, there are bright building materials, for you should not be hunched over in grief—you should be uplifted in honor.Dartsya Veretyuk, author of the “Pantheon of Heroes” concept in Ternopil

In Ternopil's “Pantheon of Heroes,” where over 200 Ukrainian soldiers are already buried, the monuments are made from light sandstone. The appearance of the cemetery is modest and not overloaded with unnecessary elements; the graves are uniform. The main reference was the shape of the memorial sign from the memorial on Mount Makovka to the soldiers of UCC. This is the first military memorial built after the battles of World War I, in which Ukrainians participated in May 1915.

Unfortunately, there are few good examples. Although cautious trends are observed, as more and more local governments are announcing competitions for the arrangement of these military sections in cemeteries. Sometimes, the results of the competitions yield decent solutions. Yes, they are quite fragmented, not cohesive, but there are already some ideas and good solutions.Ivan Shchurko, architect-planner

Memorialization Without Clear Rules

The construction of memorial cemeteries in Ukraine is still not regulated. The only guidelines local communities can follow when commissioning military cemeteries are the recommendations from the Institute of National Memory. These began to be developed after Russia's invasion in 2014.

The recommendations do not mention the type of monuments. They merely state that military burials should be distinguished by pathways or green landscaping, have sufficient distance between burials, and include a space for a common monument to fallen soldiers and for the installation of a flagpole for the national flag. Additionally, the location of the military burial section should be marked on the cemetery layout so that it is visible upon entering the cemetery.

I have read these recommendations. Unfortunately, they were not ideal; they were still quite raw, in my subjective opinion. But the very fact that such recommendations emerged was already very positive. It was one of the first important steps toward regulating this area, and it is good that this step was indeed taken by the Institute of National Memory. Clearly, they can and should be improved.Ivan Shchurko, architect-planner

Recently, the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory announced a study which, among other things, showed that most experts do not feel that the state is conducting a systematic policy in the field of war memorialization.

“This is a signal for us as a government body,” said UINP head Anton Drobovich, commenting on the experts' findings. He noted that the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory has held several roundtable discussions with the relevant parliamentary committee this year. Officials have developed elements and foundations for a national policy in the field of memory.

The impetus for dialogue about what a military cemetery should be like was the construction of the National Military Memorial Cemetery. With the emergence of this project, experts began to discuss and debate how to regulate this issue. Specialists are currently discussing what the format of tombstones should be and what the structure of military cemeteries should look like.

Military necropolises could become important historical markers of Ukrainian land, not just burials that concern only the relatives and friends of the fallen. If memorial complexes are created at such sites, it would bring the theme of war beyond the bubbles of the military and families of fallen heroes.Darka Hirna, Ukrainian journalist, documentary filmmaker, and head of the Center for Research of the Liberation Movement

Creativity or Unification?

Despite the lack of systemic solutions, there is a certain conflict in Ukraine between so-called folk and national memorialization, as indicated by the aforementioned UINP study.

On one hand, according to Anton Drobovich, there is a strong demand for a state structural policy, “that will explain how things should be done and provide guidelines.” On the other hand, there is a demand for individualism, so that “the state, so to speak, knows its place and does not interfere.”

An example of this is the legal disputes of the Stadnikov family, who disagree with installing a monument “like everyone else,” as provided for in the “Pantheon of Heroes” project. Among the uniform white tombstones, the family wants to place a bronze full-length statue of their son against a backdrop of black granite. The court proceedings have been ongoing for over a year.

The authorities are trying to determine whether monuments should be uniform and what they should look like. Currently, the Ministry of Culture is working on a law that will define what a place of memory is, says Natalia Voitsechuk, director of the Department of Cultural Heritage. The state wants to establish this status so that territorial communities can follow legal norms when planning military cemetery construction.

The war is ongoing, and there will be many such places. And when the war ends, in those areas where the frontline