Plants "whisper" beneath your feet: you may be completely unaware of the reasons behind this phenomenon.

You may not have considered that your tomato plant in the garden can communicate with its neighbors by sending specific "messages." While scientists now certainly understand that there is an exchange of information among plants, the reasons behind it may not be immediately obvious.

For instance, the notion that a plant intentionally warns its neighbors of danger may be misguided. A new study has been published in the journal PNAS.

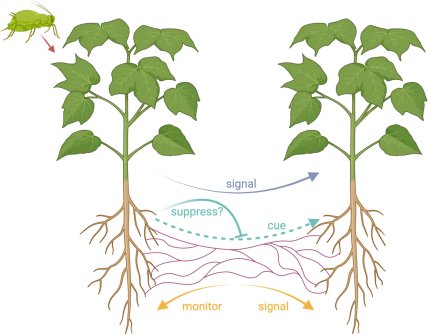

Most plants have a fungal symbiont (mycorrhiza) that connects to their roots. In this arrangement, the fungus supplies the plant with minerals extracted from the soil, while it receives water and sugars in return.

For over thirty years, the scientific community has debated whether mycorrhiza serves not only as a source of nutrition but also acts as conduits for signals to other plants. Recent research supports the idea that this is not far from the truth.

However, while previous assumptions suggested that plants could warn each other of threats, the new study indicates that there might be something amiss with this idea.

The primary evolutionary reason is that if a "distress signal" is sent, other plants will be able to prepare for an attack by pests or herbivores. However, in this case, the benefit would accrue to the plant receiving the signal, rather than the one sending it. This means that the sender is likely to lose the evolutionary race to its neighbors, who will be ready for the attack and thus remain unscathed.

In this scenario, only the most selfish plants should survive. Alternatively, they could develop a mechanism for transmitting "fake news" that would lead their neighbors to expend resources on defense and thereby weaken the "deceiver." Ultimately, this would result in no one responding to such signals.

But in theory, while in practice scientists observe that the exchange of signals continues, suggesting that the underlying reasons may be different. In the new study, researchers present two hypotheses.

The first suggests that plants cannot control the signal when damaged. For example, during an attack, a plant may release chemical compounds into the air that will be perceived by another plant. In this case, it resembles a kind of "cry of pain" that cannot be suppressed.

The second option posits that the signals are exchanged not by the plants themselves, but by their symbiotic fungi. In this case, everything appears more logical, as the fungus has a vested interest in preserving its symbionts. Or more accurately, "its symbionts," since a single fungal network can connect multiple plants. If one plant dies, the others will have time to prepare, and the fungus will not lose everything.

Additionally, experiments have shown that the network does not always transmit signals. For example, it may ignore an attack by pests if it "deems" it insignificant.

This means that while the transmission of distress signals among plants does occur, it does not necessarily imply that they are "communicating" with each other. It is quite possible that a completely different organism is responsible for this.

As previously reported, scientists have ventured into the depths of Lake Enigma in Antarctica. Despite being located under several meters of ice, it harbors a thriving ecosystem that has never been seen before.