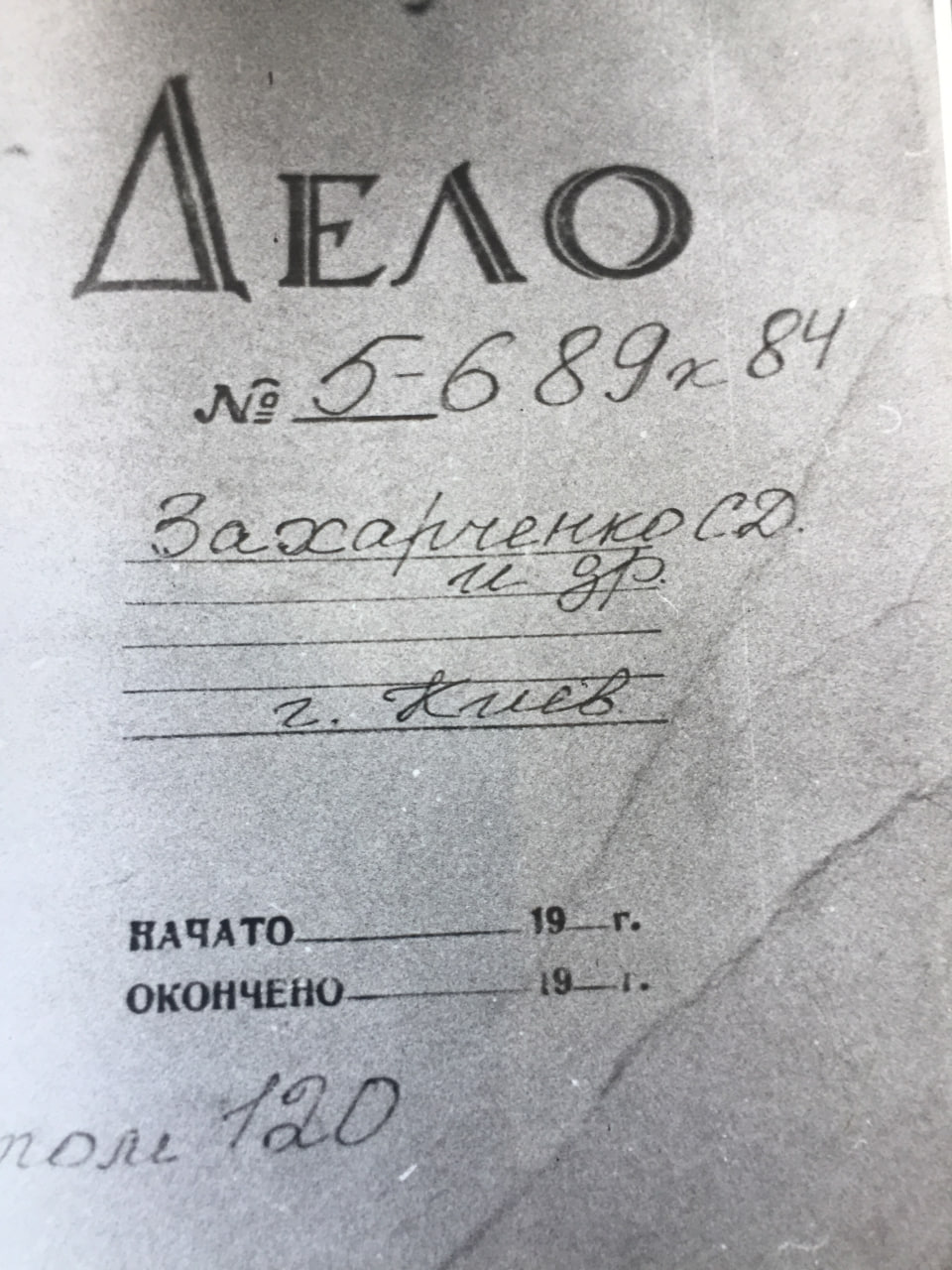

Unique cases related to very notable events from the past are preserved in the archives of Kyiv. One of these, numbered 5-689 k 84m, consists of 120 volumes of materials from a criminal investigation and court verdicts concerning trade workers in Kyiv from four decades ago.

Over 250 officials are implicated, having been convicted for "bribery, embezzlement of socialist property, and deceiving customers."

Never before had Kyiv experienced such a colossal "cleaning" of the trade sector from those who "hindered the people from building a communist future."

In April 1984, in the newspaper "Soviet Trade," Deputy Prosecutor General of the USSR Ivan Chermensky published an article titled "There Will Be No Leniency." At the beginning of the article, he raises the topic of accusations:

“For an extended period, a group of swindlers, bribe-takers, and embezzlers operated with impunity in a number of trade enterprises and organizations in Kyiv. Taking advantage of the negligence and leniency of some officials, unscrupulous individuals from trade enterprises such as 'Gastronom,' 'Universam,' 'Kyivavtomattorg,' and others deceived customers and engaged in other abuses, appropriating significant sums of money.”

Whom did this high-ranking servant of the regime target?

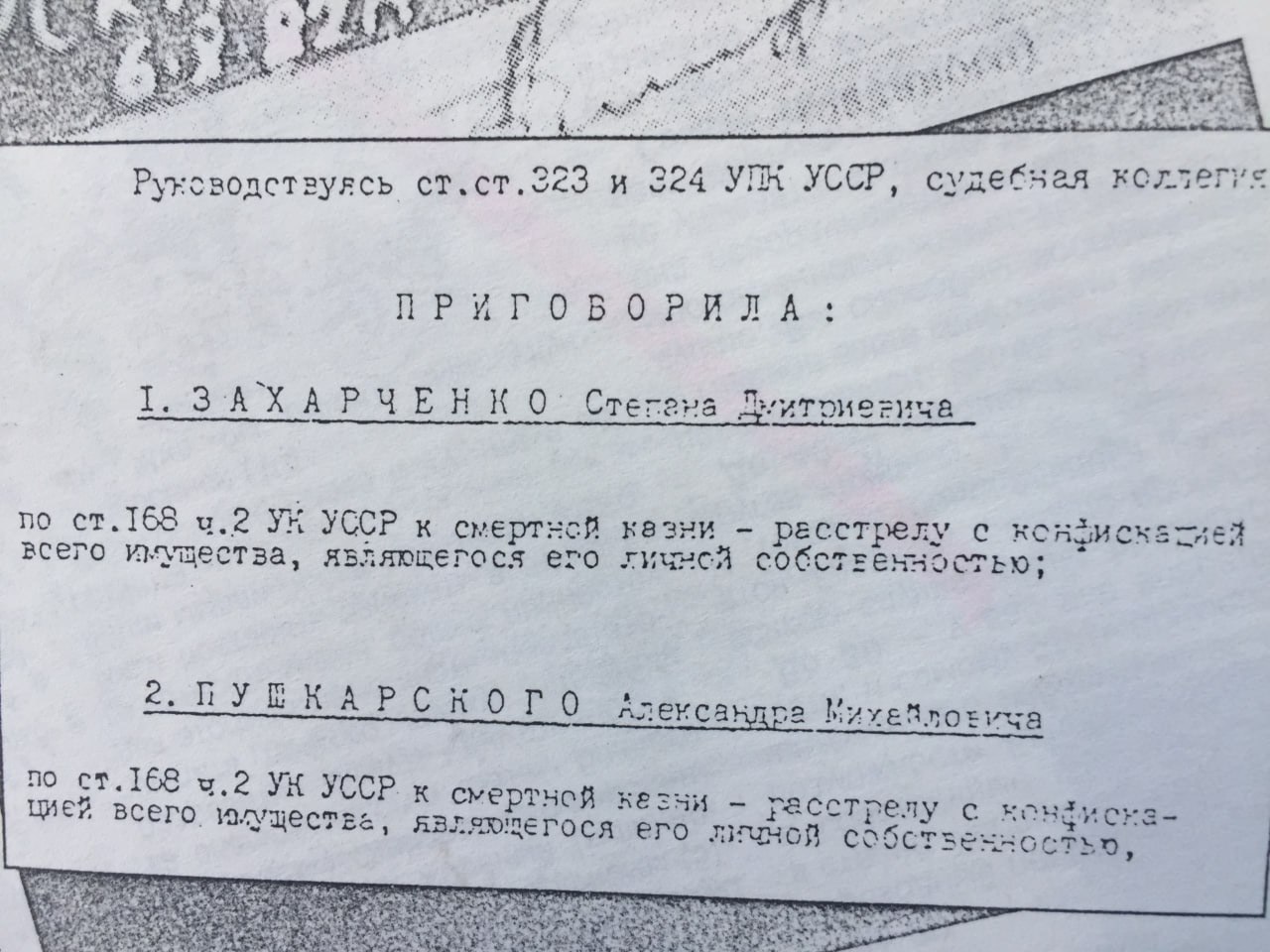

“Among those demanding bribes were the deputies of the head of the Main Trade Directorate of the Kyiv City Executive Committee, Shypuk and Kutsenko, the director of 'Kyivavtomattorg,' Pushkarsky, the director of one of the trade enterprises, Zakharенко, and others.”

The totalitarian system continued to crush those pointed out in the Kremlin with its merciless roller. The years 1982-1984 marked the reign of the KGB monster Yuri Andropov, who took the seat of General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from Leonid Brezhnev. The KGB officer Andropov set out to "restore order." In Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, high-profile trials against "embezzlers" made headlines. In Moscow, the director of the main gastronom 'Yelyseevsky,' Yuri Sokolov, was sentenced to execution for bribery, and resonant trials against trade directors spilled over to Rostov-on-Don, where 76 trade workers, led by the head of the city trade executive committee Bobrov, were sentenced (the verdict – death penalty). The head of the Main Trade Directorate in Moscow, Petrykov, received a 15-year prison sentence.

The regime needed new victims; it was also interested in Kyiv to demonstrate the scale of its total fight. The question was at what level the exposure would stop. Of course, the top of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, led by Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, was beyond the reach of the "sword of justice." However, reaching the level of the Ministry of Trade of the Ukrainian SSR and touching the trade chiefs of Kyiv from the city executive committee seemed to be the target.

Today, we do not attempt to justify anyone, proving that someone was honest while someone else was not. We recount the exceptional circumstances and sensational facts of that era, the secrets of the archives, and ultimately a period in our history when everything was distorted, and human rights were merely an empty sound. I had to study these 120 volumes of a little-known trade "case."

The investigation applied such harsh and Jesuit pressure on potential figures in the case, that many broke under the strain. The Deputy Minister of Trade of the Ukrainian SSR, Stepan Verhun, committed suicide, as did the first secretary of the Podil District Party Committee. Dozens of trade workers, under threats and blackmail during interrogations, were forced to give false testimonies, as even the slightest offense could land them in prison.

The former deputy head of the Main Trade Directorate of the Kyiv City Executive Committee, Leonid Shypuk, with whom I met after his release from prison and discussed this topic, told me that the investigation “needed Stepan Verhun, so they took those who worked with him or crossed paths with him.”

On August 20, 1982, the first investigative operational group was created in Kyiv, consisting of 60 law enforcement officers. The leading roles were taken by a team of investigators from particularly important cases under the Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR.

Arrests were underway throughout the city. Meanwhile, in the newspapers, "outraged representatives of factories and plants" demanded in collective appeals to "harshly punish the bribe-takers." This was also a kind of new Stalinism in KGB "packaging." Investigators committed a significant number of human rights violations, but no one paid attention to this. For instance, on December 21, 1982, the head of the Department for Combating Embezzlement of Socialist Property of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR, Ishchenko, reported to Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR Hlukhu that his subordinates "conducted a search in the apartment of the store manager Tkacheva without the prosecutor's authorization."

At that time, more than fifty trade workers awaited accusatory verdicts in the detention center, many of whom were salespeople, locksmiths, and mechanics. Even entire families could be thrown behind bars. This happened to the family of the head of civil defense at 'Kyivavtomattorg.' The wife of this official, a store manager, was accused of "stealing 221 aluminum spoons, 128 glass goblets, 46 cups, and 30 porcelain bowls." But as Alexander Pushkarsky later recounted to me, this woman kept these items at home for safekeeping and occasionally replenished the poor store inventory with them. Not long after being released, the unfortunate woman passed away.

It was a terrible era. People were broken like matches.

Here’s what happened to the then manager of store №754 of the Podil District Trade Enterprise after his arrest. The investigator recorded in the interrogation protocol: “During a search of the suspect, a ring was found on the ring finger of his right hand, which, according to him, had not been removed for years.” The investigator tried to take the ring off but couldn't. He then made an extraordinary decision – issued a special order stating: “To instruct specialists from the forensic department of the Kyiv City Executive Committee to remove the ring from the finger of the suspect…”. The store manager was forced to write an unusual receipt: “I agree to the removal of the ring through cutting (sawing).” Nine years of imprisonment was the court verdict. By the way, almost all store managers received severe sentences.

The investigative group made great efforts to uncover large caches of gold and valuable items. They suspected that some store managers had hidden their gold reserves in a house on the Rusanyivska embankment, transferring it for safekeeping to a trusted person. During a search, 30 items that appeared to be valuables, as well as checks and bonds, were found in a fireplace. However, the examination established that many of these were not precious metals, although some were confirmed as gold crosses, for example.

In August 1983, when a little over six months remained before the verdict for the Kyiv trade leaders was announced, the investigators reported to their superiors about "great successes in the fight against embezzlers of state property and bribe-takers":

“...Cash and valuables worth over 270 thousand rubles were confiscated, and 103 thousand 435 rubles were voluntarily contributed by the suspects to the treasury, along with items of precious metals worth 27 thousand rubles, and property worth 60 thousand rubles was described…”

The investigative group wanted to report on catching the "big fish," focusing on Verhun, Zakharchenko, Pushkarsky, and some others. Rumors circulated in Kyiv about the luxurious lives of trade managers; for instance, someone heard that in Pushkarsky's apartment, even the door handles were supposedly made of gold, and the bathtub was allegedly "made of crystal." But this was a lie. When they came to search Pushkarsky's residence (he lived with his family near the 'Ukraina' Palace), the investigators were very surprised: the door handles were made of bronze and cost 2 rubles and 50 kopecks at that time. There was no "crystal bathtub" in Pushkarsky's home.

Alexander Pushkarsky was detained on September 23, 1982, at the premises of the Prosecutor's Office of the Ukrainian SSR. On May 22, 1984, the judicial panel on criminal cases of the Kyiv City Court announced the verdict – death penalty with confiscation of personal property. On December 5, 1984, the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, Valentina Shevchenko, signed a decree pardoning Pushkarsky – the death penalty was commuted to 15 years of imprisonment. He was sent to an extremely harsh camp – "IvdelLag" in the Russian hinterland.