"Has anyone questioned why there are so many suicides in the military? What’s wrong with the psychological reform in the armed forces?"

Amid critical fatigue in the army, the significance of psychological support for soldiers, which has previously received little attention, seems to finally be recognized. The Commander-in-Chief promised a reboot of this direction, and the Ministry of Defense has established a specialized department. The old system of moral and psychological support (MPS) has recently been replaced by the personnel psychological support system (PPS).

Does the change in name imply a shift in old approaches? Why has the number of military psychologists increased while the quality has not? How does this affect the number of SOCH? Why is positive experience in brigades more of an exception than a rule? What does the Ministry of Defense say, and how did the reform almost go awry — in the material from hromadske.

“There is no brigade where all psychologists are qualified”

Currently, at the brigade level, there are combat stress control groups that work with soldiers immediately after combat missions and are tasked with identifying those in need of recovery.

In parallel, psychological support and recovery groups have been established at the battalion level.

Additionally, each brigade is required to deploy a psychological assistance point — a sort of “stabilization point” on the path to further rehabilitation.

This sounds fantastic. However, in reality, this more extensive system faces a shortage of specialists.

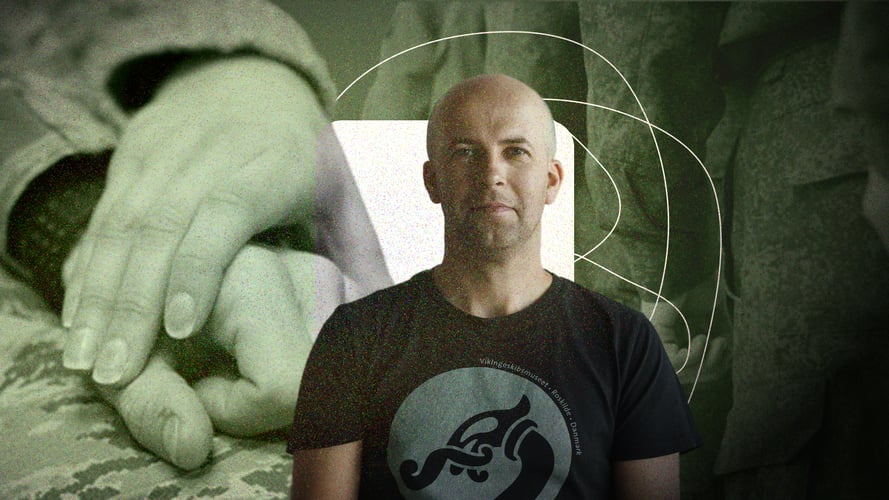

“The reality is that, firstly, you can't find that many military psychologists. If it was difficult to find five psychologists for a brigade before, then it became ten, and now it’s several dozens. Where can we get them? I have yet to meet a brigade that has ten qualified psychologists in such positions,” asserts Oleg Gukovsky, a psychiatrist and now the head of the combat stress control group in the 67th separate mechanized brigade, in a conversation with hromadske.

The idea is good. But the worst part is the substitution of concepts. Because out of several dozen officer-psychologist positions, there are literally a few with education and experience. The rest are people with completely different backgrounds.Oleg Gukovsky, head of the combat stress control group in the 67th separate mechanized brigade

According to Gukovsky, the problem is that those entering the new positions are mainly the same personnel who were part of the previous moral and psychological support system, or as they are called, “MPS officers” with a certain “political officer” tradition.

“Their discussion of psychological support as such was non-existent and there was no requirement for psychological education. Their role was focused on educational work and organizational tasks of the deputy commander of a battery or battalion. Then they were retrained. So the name changed, but the essence did not,” adds Natalia Hrytsiuk, an officer in the personnel psychological support unit of the 128th mountain assault brigade.

Some of these psychological support groups would be more accurately described as legal support groups. Because, in fact, they mainly deal with service investigations. That is, what the “MPS officers” did in their companies. That’s all.Oleg Gukovsky, head of the combat stress control group in the 67th separate mechanized brigade

Psychologists in the army: responsibilities and common sense

No matter how many attempts are made to reboot psychological support in the army, another widespread problem mentioned in most units is the incompatible workload with the position. This particularly concerns service investigations.

Suicides, unauthorized absence, desertion, loss of property, missing persons, etc. — the responsibility for managing these cases mainly falls on officers from the same psychological support and recovery groups. Although this contradicts common sense. Because, as an officer in one of those groups stated, it turns out that “the one who provides you with psychological help can also punish you.”

Yet there are no official duties requiring them to conduct service investigations. This is more of a work necessity or a relic. Some brigades manage to separate these responsibilities. It all depends on the understanding and will of the command.

“According to Order 305, these investigations are generally prohibited (for personnel psychological support units — ed.). None of our people do them; the chief sergeants handle that. The only exception is suicide. Because that genuinely concerns the psychologist. But in many brigades, these investigations are carried out. Well, of course, then they won’t have time to support people,” says Natalia Hrytsiuk about the work in the 128th mountain assault brigade.

The experience of the 128th in the psychological rehabilitation of soldiers is more of an exception than a rule. They assure that the command facilitates the recovery of personnel. Therefore, soldiers are sent to rehabilitation centers or given time off at the first opportunity. This year, hromadske filmed a story about their psychological assistance point. Currently, it has been adapted to accommodate more people.

“We have this very developed. We go ourselves and work with people. Our psychological assistance points are located in every unit. For example, if a person is found with reactive anxiety and the like — they are immediately taken to PPS in the unit, all necessary screenings are conducted, and then they are transferred to us (to the brigade psychological assistance point — ed.) for 7 days. So in total, a person spends 10 days in rehabilitation, can switch gears, get out of this muck, and breathe out,” says Natalia.

But I know that there are bitter experiences in other brigades. There are those where there is no concept of a psychological assistance point at all.Natalia Hrytsiuk, officer in the personnel psychological support unit of the 128th mountain assault brigade

“I don’t know what psychologist here can do anything”

In other units, the situation is indeed different. A hromadske interlocutor in one of the battalions responsible for personnel psychological support states that in a month they can only afford to send two or three people for recovery, although the need is for dozens.

“It would be good to send 20-30, but we can’t. Because we simply lack people. We’re improvising as best we can. In our psychological support group, there are 4 people per battalion. But, you see, if people with ten years of combat experience are also refusing to perform tasks, then I don’t know what psychologist here can do anything,” says the deputy commander for PPS.

It’s one thing to talk in offices and write concepts, and another to talk to people who don’t know if they’ll make it out of a combat task or not, and if not, whether they’ll be pulled out at least dead?deputy commander of the infantry battalion for personnel psychological support

The senior officer admits that although he currently oversees personnel psychological support, he does not have a psychological education.

“At the beginning of the war, I was the deputy commander of the battalion for personnel. Then — the deputy commander for moral and psychological support. And since July, I’ve been the deputy commander for personnel psychological support. However, I do not have professional psychological education. And there is no talk of advanced training for senior officers. Without proper training, all of this is just bubbles.”

This confirms the story of the shortage of specialists. The head of the psychological support and recovery group in this battalion has a psychology degree from 12 years ago and has never worked as a psychologist. In the summer, he only completed a one-month advanced training course.

Reform in question?

For example, the Military Institute of the Shevchenko National University prepares those with a civilian psychology degree in a month and a half. Thus, they receive military education and an officer rank.

As of March 2024, there is an order with requirements regarding the profile education of psychologists in relevant positions.

“But certain appointments still occur bypassing this. We need to work on this. Writing a document is not enough. It’s necessary to ensure that it is implemented correctly,” acknowledges Valentina Obolenets, head of the Psychological Support Department of the Ministry of Defense.

She agrees that psychological reform in the army hinges on both the psychological training of all military personnel and the education of staff.

“If we do not train specialists, nothing will happen. After all, if we call a mouse a hedgehog, it will not become a hedgehog. Because this is a complex issue. Everything begins with basic general military training, where there is a psychological component. And then there are questions of training and educating specialists with civilian psychological education,”</